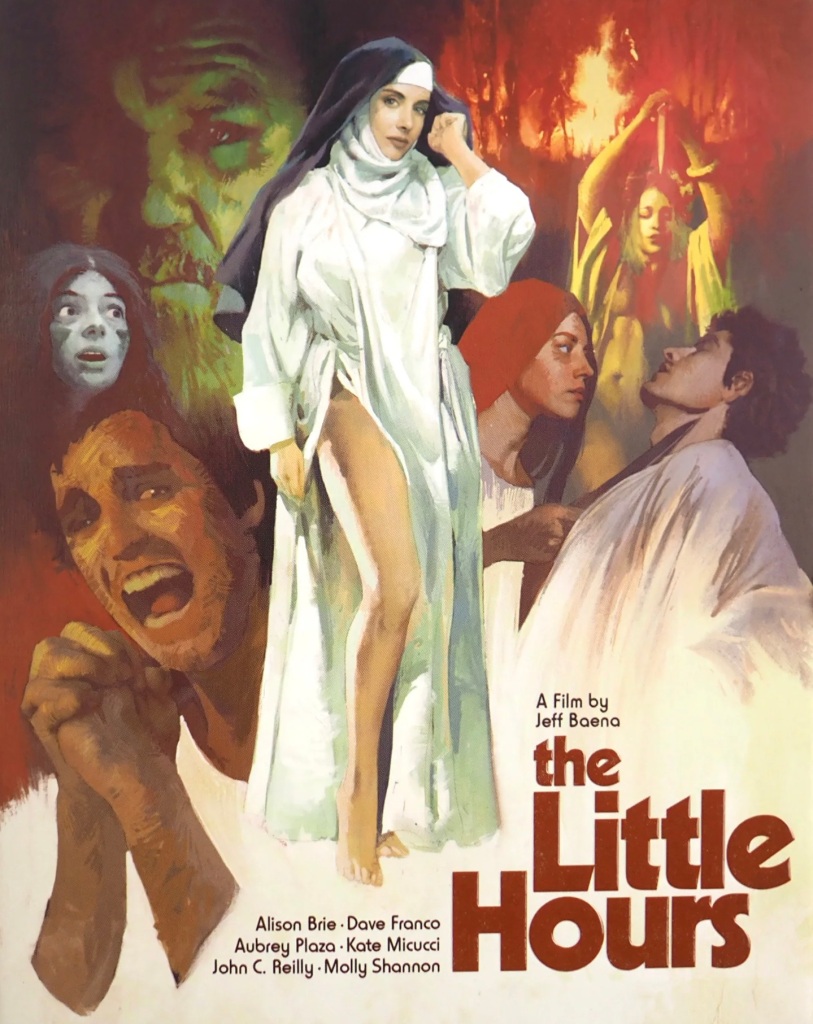

Set in a mid-14th century convent in Garfagnana, Italy, The Little Hours subverts modern viewers’ expectations of Catholic convent life in order to create an absurd comedy. The film follows three young nuns, Sisters Alessandra, Fernanda, and Genevra, and is based on stories from The Decameron, a collection written in the 1300s. One of the major themes explored is the evolution of the nuns’ sexuality, which is innately comedic given that nuns are supposed to be celibate. In this way, the film “queers” the writings of The Decameron. “Queering” is an academic practice that functions to “contest medieval representational practices across sexual, gender, and class lines” and “produce readings of medieval texts that trouble our assumptions about medieval culture and textual practices” (Lochrie 1997). For comedic purposes, the director takes “queering” to the extreme; the nuns have sex with laymen, priests, and each other, and—in perhaps the queerest aspect of the film—practice witchcraft. Therefore, The Little Hours relies heavily on its setting in a medieval Italian convent for its comedy, humorously subverting modern assumptions about the Catholic female experience in the Middle Ages by emphasizing queer expressions of sexuality—specifically, by weaving a story of Catholic nuns as lesbian witches.

In order to set the scene, it is important to know what type of sexuality was allowed for medieval nuns. Devout medieval religious women generally experienced sexuality as “interior” and “experiential” through “the materiality of space and visual imagery” rather than as an innately physical process (Gilchrist 2005). This causes issues to arise when attempting to apply modern ideas of sexuality to these women because of the assumption that physical contact with another animate individual is necessary for “normal” sexuality. Rather, medieval religious women experienced their sexuality through asceticism. Chaste and devoted nuns renounced their personal identity and individuality, dedicating their body to Christ (Gilchrist 2005). This extreme sacrifice is in stark contrast to the obvious self-interest displayed by the nuns in The Little Hours; each of the three main characters seek out sensual pleasure, whether it be by seducing the gardener (45:48), taking a love potion in order to have sex (1:00:40), or performing a fertility ritual at a coven gathering (1:06:08).

An additional aspect of medieval monastic sexuality that actually is present—but not effective—in The Little Hours is the practice of containment in a convent, based on the belief that nuns be physically enclosed to ensure their virginity. The convent is indeed secluded and enclosed by a large gate (56:06), but this does not prevent the precocious and sexually driven nuns from exploring and realizing their sexualities by using the facilities and people available within the convent. Notably, Sister Genevra’s realization of lesbian sexuality occurs via a process of consumption, instead of abstinence: by eating a love potion and attempting to have sex with the male gardener, she confirms to herself that she in fact only likes to have sex with women (Gilchrist 2005). Therefore, while chaste medieval nuns practiced their sexuality by restricting food via “holy anorexia” in order to have sensual visions of Christ’s body, Genevra creates her own spiritual experience via an opposite process. Essentially, the nuns in The Little Hours exemplify everything that devout medieval nuns were not supposed to be. The creators of The Little Hours take this juxtaposition to the extreme (as shown in the stills below), using the absurdity to fuel their comedy.

One of the main ways The Little Hours queers its storyline is by exploring lesbian sexuality within the convent. Medieval lesbians have been “twice marginalized” by academia and popular culture, for they have been historically omitted from women’s and queer studies by virtue of their sexuality and gender, respectively (Murray 2000). Queer medieval women are made even more obscure by a shortage of primary sources because any female activity that excluded men was generally not considered noteworthy at the time (Karras 2006). However, there is evidence, although scant and sometime tenuous, for expressions of queer sexuality in medieval convents. For example, Catholic mystics often expressed sexual attraction to the feminized body of Christ (Lochrie 1997). Oftentimes, the wound in Christ’s side inflicted by a spear during his crucifixion was portrayed as a vulva, with both male and female mystics focusing on this image specifically in their adoration. Devotional writings by religious women show that this (vaginal) wound specifically was an important object of religious sexual experience (Lochrie 1997). Furthermore, Church leaders condemned lesbianism, particularly between nuns, showing that they were aware that this was a possibility within convent life (Murray 2000). Therefore, lesbian sexuality was a reality in medieval religious life.

The Little Hours queers the medieval stories of The Decameron by giving lesbian sexuality a spotlight; for example, viewers watch the evolution of Genevra’s coming out first as she witnesses Sister Fernanda kissing another woman (43:47), has sex with Fernanda (44:28), and finally realizes she is solely interested in women (1:02:20). Any primary medieval sources on lesbianism tend to simultaneously condemn and trivialize it. Penitentials, handbooks written as guides for which penances priests should assign during confession, did not regard lesbianism to be as serious a sin as other sexual transgressions unless the participants used a phallic device, for this was assumed to be an attempt to usurp the power of men (Bennett 2000; Karras 2006). For example, one penitential assigned the same duration of penance for lesbian sex as it did for masturbation (three years), emphasizing that “real” sex was phallocentric; another prescribed a penance of seven years for sex between nuns “using an instrument,” but it did not make clear whether it was the religious status of the women or the use of the instrument that warranted this harsher punishment (Murray 2000). This attitude about lesbian sex is mirrored in The Little Hours: when the bishop lists off Sister Genevra’s sins, he says, “envy, fornication, homosexuality… that’s the same as lying with a woman, but we separate those” (1:11:47). This line, comedic to modern audiences, reveals the intricacy and absurdity of proper Catholic sexuality in the Middle Ages.

Similarly, popular secular writing used lesbianism as a punchline. A comedic poem written in the early Middle Ages called Le Livre de Manières (The Book of Manners) reveals this attitude: “They’re not all from the same mold: / one lies still and the other makes busy, / one plays cock and the other the hen / and each one plays her role” (Murray 2000). In The Little Hours, queer sexuality is also part of a joke, as Sister Genevra’s sexual awakening is used as comic relief. Her attempt to have straight sex ends up with her tripping on drugs and proclaiming herself as gay (1:02:20), and her drug-fueled argument with Sister Alessandra over their claim to the gardener and her sexuality is funny because neither of them, as nuns, are technically supposed to be sexually attracted to anyone (1:09:37):

Genevra: I saw him first.

Alessandra: What do you mean, you saw him first? You don’t even like men! You’re sexually attracted to women.

Genevra: I am sexually attracted to men!

Queer sexuality as a punchline is not new, as evidenced by Le Livre de Manières, but these two comedic pieces utilize lesbianism differently. In Le Livre de Manières, the punchline is the entire joke: sex between women is ridiculous because they are trying to be like men. In The Little Hours, Sister’s Genevra’s storyline does serve a comedic purpose, but it also adds to a story of female sexual power and sisterhood, as her friends do not reject her for her orientation. The Little Hours’ queering endeavor dives deeper as it explores an even more taboo expression of female sexuality—witchcraft.

Queer sexuality and witchcraft are innately linked in The Little Hours, with both driving the characters’ individual and group identities forward. This connection is not accidental; lesbianism and witchcraft were also linked in medieval thinking, for both were seen as deliberate, unnatural rejections of proper female sexuality. During the mid- to late Middle Ages, the popular idea of witches shifted from those who simply practiced magic (a less gendered and more benign act) to women who worshipped and/or slept with the devil (Karras 2006). Thus, witchcraft had gained a distinctly anti-Catholic dimension by the period in which The Little Hours is set, making it the perfect contextual foil for a convent. Malleus Maleficarum (in English, Hammer of Witches) is a text written by German friars in the 15th century that exemplifies medieval Catholic ideas about witches. Malleus Maleficarum imagines witchcraft as an innately feminine issue by linking the practice to “feminine” characteristics; according to the authors, women were “credulous,” “impressionable,” weak, and possessed of “slippery tongues,” all of which made them especially susceptible to falling in with the devil (Broedel 2018). Women were thought to employ magic because it was their only way to exert power over men; therefore, Malleus Maleficarum, like The Little Hours, acknowledged a gendered power imbalance that brings about witchcraft. The difference is that The Little Hours views witchcraft as a positive act of female empowerment for the main characters. For example, Sisters Alessandra and Genevra stumble upon Sister Fernanda’s fertility ritual and see naked women dancing around the fire (1:04:22). Newly emboldened by her sexual awakening and fueled by drugs, Sister Genevra also strips and joins in the dancing, shedding the previous meekness that drove her actions in the first part of the film. Similarly, when the bishop attempts to list off Sister Fernanda’s sins, including homosexuality and witchcraft, she rolls her eyes (1:13:18). Certainly, witchcraft has empowered the nuns and given them agency—exactly what medieval writers feared.

Malleus Maleficarum singles out love magic as particularly feminine and dangerous, framing this type of magic as an issue because it results in “unnatural” (queer) sexuality (Broedel 2018). Thus, it is only natural that the magic practiced in The Little Hours is love magic. Sister Fernanda makes a potion out of the plant belladonna to seduce the gardener (49:56) and later attempts to sacrifice him in a fertility ritual, chanting “for so it was placed when the goddess embraced / the horned lord, our god who taught her the word / which quickened the womb and conquered the tomb” (1:06:08). However, when Sister Genevra attempts to use the same belladonna potion, she uses it incorrectly and ends of high off its hallucinogenic qualities (1:00:40). This scene reveals the absurdity of medieval alarm over love magic. However, even though Genevra’s attempt at witchcraft is unsuccessful, she still expresses queer sexuality. The viewer is left with a question that haunted the medieval imagination—which comes first, aberrant female sexuality or witchcraft? The answer, according to the Malleus, is neither: “the relationship between sexual deviance and witchcraft was reciprocal: disordered sexual relationships engendered witches, and witchcraft, in turn, disordered sexual relationships” (Broedel 2018). Thus, although Malleus Maleficaurm does not explicate extensively about lesbianism, witchcraft essentially becomes interchangeable with queerness because both are disruptive to the social order. This disruption is exemplified in one of the final scenes in The Little Hours, when Sisters Alessandra, Genevra, and Fernanda sit in a field and have a moment of reconciliation after the chaotic fertility ritual (1:17:09):

Fernanda: I’m sorry I didn’t tell you I was a witch. But honestly, I thought eventually I could turn you all into witches, and you’d join my coven, but I know that sounds stupid.

Genevra: You really think I could be a witch?

Fernanda: Yeah.

The setting of this scene is ironic because the women have redonned their habits and are sitting amongst white flowers, a color traditionally symbolic of purity and virginity. This visual juxtaposes with the sexual and “sinful” acts the viewer has watched the nuns undertake, thus pulling together the queering work done in The Little Hours. Despite their conflicts throughout the film, Fernanda and Genevra smile at each other, confirming that their journey has only brought them closer, rather than damning them to hell as the Church would have them believe. Fernanda believes Genevra could be a witch, thus affirming her feminine power and queer identity. The Little Hours’ link between lesbianism and witchcraft in not novel, but rather pulls from a deep history of queerness and subversion that allows the film to be simultaneously comedic, dark, and touching.

Works Cited

Bennett, Judith M. 2000. “‘Lesbian-Like’ and the Social History of Lesbianisms.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 9 (2): 1–24.

Broedel, Hans Peter. 2018. “Witchcraft as an Expression of Female Sexuality.” In The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft: Theology and Popular Belief, 167–88. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Gilchrist, Roberta. 2005. “Unsexing the Body: The Interior Sexuality of Medieval Religious Women.” In Archaeologies of Sexuality, 89–103. Routledge.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. 2006. “Women Outside of Marriage.” In Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others, reprinted, 87–119. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lochrie, Karma. 1997. “Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies.” In Constructing Medieval Sexuality, 180–200. Medieval Cultures 11. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Murray, Jacqueline. 2000. “Twice Marginal and Twice Invisible: Lesbians in the Middle Ages.” In Handbook of Medieval Sexuality. New York: Garland Pub.: Routledge.